Have you ever experienced that sticky feeling in the air on a hot summer day? Or noticed how the weather can drastically change just when you thought it was pleasant? This phenomenon is intricately tied to the concept of humidity, and one of the central questions that arise is: Does humidity rise or sink? This inquiry not only piques curiosity but also delves into the fundamental principles of meteorology, thermodynamics, and fluid dynamics. Let’s embark on an exploration of this atmospheric enigma.

First, let’s establish what humidity actually is. Humidity refers to the concentration of water vapor present in the atmosphere. It is often quantified in terms of relative humidity (RH), defined as the percentage of moisture in the air compared to the maximum amount of moisture that the air can hold at a given temperature. Fascinatingly, warmer air can contain more water vapor than cooler air, which is crucial to understanding the dynamics of humidity.

At first glance, the intuitive answer might lean towards the belief that humidity, being moisture-laden, rises. After all, we often visualize water vapor as something airy and buoyant. However, this principle requires a more nuanced examination. When air is heated, it expands and becomes less dense. Dry, warm air indeed rises due to its lighter nature. However, the story takes an intriguing twist when we factor in the weight of the water vapor.

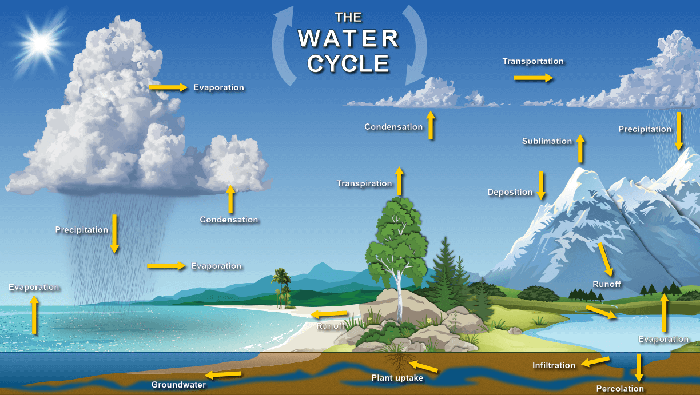

Despite water vapor being lighter than many gases, it exists in a gas state where it does not simply “float” to the top. Here’s where the challenge lies: cooler air is denser and will sink. But what happens when cool air interacts with warmer, humid air? The moisture that rises in warm air can lead to the formation of clouds and precipitation, demonstrating a complex interplay rather than a straightforward ascent or descent.

A critical aspect to consider is the role of temperature gradients. During the daytime, the sun heats the ground, which in turn heats the air just above it. This results in a continuous cycle of warm air rising and cooler air descending. In this scenario, humid air—because of its lower density relative to surrounding cool air—will typically rise. However, if a mass of humid air is not entirely warm, particularly at night or during stormy weather, it may not ascend as anticipated and can instead create localized phenomena like fog or dew.

To further complicate our understanding, let’s explore the concepts of convection currents and humidity. As warm, humid air rises, it cools, causing the water vapor to condense into tiny droplets, forming clouds. Once these droplets coalesce sufficiently, gravity asserts its hold, leading to precipitation. Here, the initial rise of humid air is followed by a descent in the form of rain, snow, or sleet. Thus, one could argue humidity “rises” during the initial phase but “sinks” during precipitation.

Additionally, different weather patterns exhibit intriguing behaviors of humidity. For instance, in tropical regions, the high temperatures and abundant moisture contribute to a stable environment where convective currents vigorously circulate. Conversely, the situation in polar regions differs significantly; cold air can be incredibly dense, and humidity behaves distinctly, often resulting in stark visibility effects like frost and ice rather than rain.

Moving from local phenomena to global patterns, let’s consider how humidity impacts weather systems around the world. Areas near large bodies of water often experience higher humidity as the evaporation of water increases moisture levels in the air. Conversely, deserts exhibit low humidity due to minimal water sources. These geographical nuances can lead to completely different local weather systems, which manage humidity in unexpected ways.

Interestingly, what about at night? Cool air from the evening can trap moisture close to the ground, leading to higher humidity readings. This situation invites yet another playful challenge: Can you predict the weather based on humidity changes in the evening? This phenomenon is not merely an academic exercise; it can aid in understanding weather forecasting and climate adaptation strategies.

Moreover, urban development has introduced a new variable to our humidity equation. Cities tend to have higher temperatures (a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect), leading to increased evaporation rates. This creates a feedback loop, where rising temperatures lead to higher humidity, which in turn can affect air quality and storm dynamics in metropolitan areas. The intricate dance between human activity and atmospheric conditions throws yet another curveball into the simplistic model of rising and sinking air.

As we ponder the question, “Does humidity rise or sink?” we realize that it is not merely a binary decision but rather a multifaceted puzzle involving temperature, pressure, and geographical contexts. While humid air can rise when heated, its descent is just as critical, especially during precipitation events and in various climates. Understanding these dynamics unlocks deeper insights into not only our weather patterns but also our responses to climatic changes.

So, the next time you feel the thick, humid air enveloping you, take a moment to appreciate this complex relationship of atmospheric forces at play. Can you identify the dance of humidity and temperature around you? Are you equipped to enjoy the nuances of weather that shift and sway based on these principles? Embrace the challenge; the atmosphere is a lively character with many stories to tell.